Everybody knows that they don’t know enough about the world.

Where people disagree though, is how much exactly they know. “Maybe I don’t know about rocket science or self-driving cars”, you might say, “but I know enough about the world”. That’s enough for me.

It sounds reasonable, but even then, there’s a good chance you may be taking too much credit. Complexity exists all around us.

Take a minute and try to explain what happens when you flush a toilet. If you’re like me, you’ll be stumped when asked to explain the principles that govern the toilet’s operation.

As Steven Slomach and Philip Fernbach tell us in The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone:

“To fully understand toilets requires more than a short description of its mechanism. It requires knowledge of ceramics, metal, and plastic to know how the toilet is made; of chemistry to understand how the seal works so the toilet doesn’t leak onto the bathroom floor; of the human body to understand the size and shape of the toilet.”

That’s a lot of crap that goes into toilets. It certainly isn’t as simple as we thought before.

The Illusion Of Explanatory Depth (Or It Just Works, There’s Nothing To Explain)

How then, can we tell how much we really know?

As we’ve just learned from the example of toilets, most of us overrate our knowledge on just about any given topic. In a 2002 study, participants were given three questions related to their knowledge of zippers:

- On a scale from 1 to 7, how well do you understand how zippers work?

- How does a zipper work? Describe in as much detail as you can all the steps involved in a zipper’s operation.

- Now, on the same 1 to 7 scale, rate your knowledge of how a zipper works again.

On average, each participant initially gave themselves a 4 on the scale. But after being asked to explain the operation in detail, the participants lowered their rating by a point or two. Having to explain something instilled more humility in the participants.

People feel they understand complex phenomena with far greater precision, coherence, and depth than they really do. This is what Rozenblit and Keil, authors of the study, call the illusion of explanatory depth.

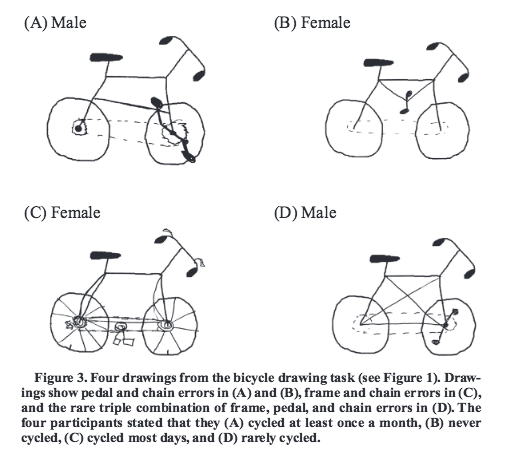

It’s not an observation that happens with just words either. In another 2006 study by the University of Liverpool, participants were asked to draw a picture of a bicycle. Here’s what some drew:

The results weren’t pretty. Over 40% of participants couldn’t do it. Many drew bicycles that would be completely non-functional.

It’s easy to mock people for their lack of understanding on how objects around us work. Yet go down a list of deceptively simple items and you’ll find that you’ll eventually encounter one you can’t explain. Exposure to ignorance is an effective way to become more mindful of unjustified confidence.

Toilets, zippers, and bicycles. What else don’t we know?

My guess is a lot more than we’d like to admit.

The Collective Hivemind

The illusion of explanatory depth can be explained by many reasons in the field of cognitive psychology.

For starters, we’re poor at causal reasoning. We reject evidence even when it’s staring at us in the face because we suffer from confirmation bias. We tell ourselves stories and appealing fictions.

And yet, the most important reason that we’re ignorant about so many things is that we don’t have to be knowledgeable. As social animals, humans have divided up labour since the days of the hunter-gatherer. In today’s knowledge economy, things are no different.

Here’s Slomach and Fernbach in The Knowledge Illusion:

“We would not be such competent thinkers if we had to rely only on the limited knowledge stored in our heads and our facility for causal reasoning. The secret to our success is that we live in a world in which knowledge is all around us. It is in the things we make, in our bodies and workspaces, and in other people. We live in a community of knowledge.”

Funny as that may sound, ignorance is the choice we’ve made.

The ability to tap on a pool of knowledge has given us a free pass to be ignorant about things we would ordinarily consider basic. We’re able to build upon what past generations have discovered, share information amongst our peers, and let future generations shape the world in ways we can’t imagine.

All this, without knowing how a lot of things work.

What’s Yours Is Mine

Like most things, the benefits we’ve gotten from dividing our cognitive labour comes with a catch.

One implication of the naturalness with which we share knowledge so seamlessly is that there is no clear defined boundary between one person’s knowledge from another’s. Here’s Slomach and Fernbach:

“We also suffer from the knowledge illusion because we confuse what experts know with what we ourselves know. The fact that I can access someone else’s knowledge makes me feel like I already know what I’m talking about. The same phenomenon occurs in the classroom: Children suffer from an illusion of comprehension because they can access the knowledge they need. It is in their textbook and in the heads of their teacher and the better students.”

Why is the sky blue? How do we know the Earth is round? What causes hurricanes and earthquakes?

Most of us wouldn’t be able to give detailed answers to the above questions, but I doubt that we consider ourselves ignorant. It doesn’t matter to us because we can find any of these answers in textbooks, encyclopaedias, or from a quick Google search.

As a collective species, we’re really intelligent. But as individuals, it appears that most of us suffer from a lack of humility. We wouldn’t survive long without other members of our community.

As Smart As We Can Possibly Be

This still begs the question: how can we get around, sound knowledgeable, and take ourselves seriously while understanding only a tiny fraction of what there is to know?

It turns out that we may be mostly living a lie:

“We ignore complexity by overestimating how much we know about how things work, by living life in the belief that we know how things work even when we don’t. We tell ourselves that we understand what’s going on, that our opinions are justified by our knowledge, and that our actions are grounded in justified beliefs even though they are not. We tolerate complexity by failing to recognize it. That’s the illusion of understanding.”

I doubt we can ever bridge this gap of knowledge. But if we’re going to try, it’s best to first recognise the difference between two types of ignorance: “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns”.

In the former category, we have things like AI, space travel, and self-driving cars. These are topics we know that we have little knowledge on, and so we’re constantly striving to learn more.

In the latter category are things that we don’t know we’re clueless about. Your guess is as good as mine on what falls under this category, but remember that it’s not just futuristic matters that belong here, but also more mundane matters like toilets, zippers, and bicycles.

The latter category is where the danger lies. We can’t do anything about something we’re unaware of. Yet if we sweep things into the second category because we have a hard time understanding complexity, the solution might just be a little more patience and humility.

I leave you with these parting thoughts from The Knowledge Illusion:

“For humans, ignorance is inevitable: It’s our natural state. There’s too much complexity in the world for any individual to master. Ignorance can be frustrating, but the problem is not ignorance per se. It’s the trouble we get into by not recognizing it.”

Ignorance is bliss, but illusion is not.